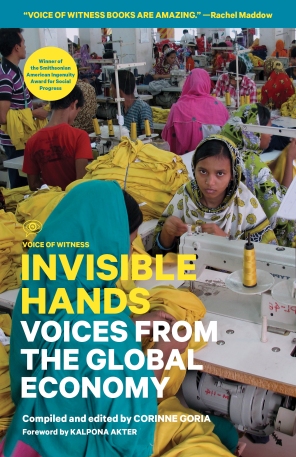

I am thrilled to announce that in a little over three weeks Voice of Witness (VOW) will publish it’s latest book, Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy and my name will be on the title page.

“The men and women in Invisible Hands reveal the human rights abuses occurring behind the scenes of the global economy. These narrators—including phone manufacturers in China, copper miners in Zambia, garment workers in Bangladesh, and farmers around the world—reveal the secret history of the things we buy, including lives and communities devastated by low wages, environmental degradation, and political repression. Sweeping in scope and rich in detail, these stories capture the interconnectivity of all people struggling to support themselves and their families. ” To read more about the collection visit http://voiceofwitness.org/labor/.

“The men and women in Invisible Hands reveal the human rights abuses occurring behind the scenes of the global economy. These narrators—including phone manufacturers in China, copper miners in Zambia, garment workers in Bangladesh, and farmers around the world—reveal the secret history of the things we buy, including lives and communities devastated by low wages, environmental degradation, and political repression. Sweeping in scope and rich in detail, these stories capture the interconnectivity of all people struggling to support themselves and their families. ” To read more about the collection visit http://voiceofwitness.org/labor/.

I first learned of Voice of Witness in 2010 while I was on a road trip with several of my best friends that I had studied abroad with in college. We stopped off in San Francisco in December and found out that Peter Orner and Annie Holmes were speaking about VOW’s latest book Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives. Already interested in checking it out, we discovered that the event was to be held at 826 Valencia – San Francisco’s only independent Pirate supply store (also a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting students with their writing skills, and to helping teachers inspire their students to write). So naturally we had to go.

Peter and Annie’s stories of working on the book were incredible and moving. I had just submitted my Fulbright application about a month earlier and as I listened to them talk about how oral history is a powerful way to address human rights issues I had a moment of clarity. I felt, with almost uncomfortable certainty, that I wanted to do something similar with my work in India. I approached Peter and Annie after their talk and nervously told them about my hopes about getting the research grant to go study cotton farming in India. I asked with some trepidation how they got involved with VOW and what had led them to working on this book. Could random, inexperienced folks such as myself suggest book topics? Was it crazy to wonder if I could ever work on a book on cotton farmer suicides with VOW? I was filled with adrenaline and a curiously potent mix of nervous confidence.

But one step at a time. I had to get to India first. I had just submitted my application and it would be months before I would hear if I had received the grant and was going to India.

By the time I finally found out that I was going to India it was April, 4 months since I’d first heard of VOW and met Peter and Annie at 826 Valencia. I was so overcome with relief and excitement that I had gotten the Fulbright that I didn’t think of Voice of Witness until a year later when I was in Kochi at a conference for Fulbright researchers and scholars to present their work. I was speaking with a friend and he asked if I had ever heard of Voice of Witness. Yes. Mmmhmm. I had. He suggested that I get in touch with them; they were compiling narratives on human rights and the global economy.

So a few weeks later I emailed Corinne Goria, the editor of this collection, and told her who I was, where I was, and what I was doing, trying to be professional about how desperately I wanted to get involved with the book. After a Skype interview to discuss how I could contribute to the book, I set off to see if I could find a widow of a cotton farmer who would be willing to be interviewed by me for several hours on several different occasions. The timing couldn’t have been better. I was poised to attend a gathering for widows in the area that weekend. Subhag, my friend and translator, was able to come with me and we mingled with the widows during their lunch at the event. I had to find someone who could answer questions with great detail, who would talk about her childhood, who could give me enough material to shape into a rich narrative. At the very end of the day Pournima and her son came up to Subhag and asked who I was.

Over the next 6 months I visited Pournima every few weeks. At first I only visited her for the interviews. But after the third interview it was clear that she was very depressed and overwhelmed by her situation. I also felt overwhelmed and unsure of how I could help to ease her situation so she could feel peace and regain a sense of hope for her children and herself. You may remember this – I wrote about it in the post “Supari.”

I shared my fears with Corinne and with Ajay and Yogini Dolke, a couple that runs the non-profit SRUJAN, and who were instrumental in helping me with my research while I was in India. Corinne encouraged me to keep visiting Pournima without interviewing her to show her I cared for her well-being. Ajay and Yogini were inspired to reach out to their network of colleagues, friends, and family to raise money to purchase a sewing machine for Pournima. For more about how we were able to help Pournima, see the “Donate to Pournima” page.

My 25th birthday party at Pournima’s house

I became friends with Pournima and her son and daughter (whose names I have omitted to honor Pournima’s wish for privacy and protection). I traveled with Pournima to the village where she grew up. I met her mother, father, sisters, brothers, nieces, and nephews. I saw her father’s cotton fields, where she spent much of her childhood. That same week Pournima found out it was my birthday and insisted that I come to her home and celebrate with her family and her neighbors. We filled ourselves with fried treats and sweets and filled the neighborhood with music and laughter.

Pournima never ceased to amaze me with her generosity. Every time I came to see her, whether or not I was coming to interview her, she fed me, gave me tea, and made sure I was healthy and happy. “You look skinny. Are they taking care of you in Mulgavan?” she would often ask.

It was hard to explain to her why I wanted to share her story with the world. “People do not know about the struggle of cotton farmers in India. It is important that they hear your story. We have to raise awareness,” I would tell her. And as soon as I would say this I would wonder how much of a difference her story could make. While she shared her story and I edited it and prepared it for the book, thousands of farmers were still killing themselves. One farmer every 30 minutes. How could this book improve this situation?

It’s a question I still live with every day – one that I am revisiting more frequently now that the book is almost available in print. I am, however, so honored to have been able to be a part of the process of helping Pournima share her story, and in that process, helping her to overcome her devastating past and start living a brighter, more hopeful life. Being a widow in India is not easy, but Pournima is strong. She is resilient. Perhaps her story can give others the strength that they need to overcome tragedy. I know her story is inspiring, and I am looking forward to see how that inspiration is manifested as more and more people get to read her words.